Article by Clive Phillpot - Manifesto I

Manifesto I

FLUXUS: MAGAZINES, MANIFESTOS, MULTUM IN PARVO

By Clive Phillpotsource: http://georgemaciunas.com/about/cv/manifesto-i/

George Maciunas’ choice of the word

Fluxus, in October 1960, as the title of a magazine for a projected

Lithuanian Cultural Club in New York, was too good to let go when that

circumstance evaporated. In little more than a year, by the end of

1961, he had mapped out the first six issues of a magazine, with

himself as publisher and editor-in-chief, that was scheduled to appear

in February 1962 and thereafter on a quarterly basis, to be titled Fluxus.

The projected magazine might well have

provided a very interesting overview of a culture in flux. Maciunas

planned to include articles on electronic music, anarchism,

experimental cinema, nihilism, happenings, lettrism, sound poetry, and

even painting, with specific issues of the magazine focusing on the

United States, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and Japan. Although its

proposed contents reflected a contemporary sensibility, its emphasis on

the publication of essays on those topics suggests that the magazine

would have been relatively conventional in presentation. But the seeds

of the actual Fluxus magazine that was eventually published

were nonetheless present, even in the first issue of the projected

magazine, since it was intended to include a brief “anthology” after

the essays.

This proposed anthology would have drawn on the contributors to La Monte Young’s publication An Anthology, the

material for which had been amassed in late 1960 and early 1961, and

which George Maciunas had been designing since the middle of 1961. In

fact Fluxus was “supposed to have been the second Anthology.” But the anthologized works projected for the first Fluxus were radically different from the articles, since they were printed artworks and scores—as were most of the pieces in An Anthology, which was finally published by La Monte Young and Jackson Mac Low in 1963.

After interminable delays, Fluxus 1

finally appeared late in 1964. But during this three-year gestation

period it had evolved dramatically and become virtually an anthology of

printed art pieces and flat, or flattened, objects; the essays had

practically vanished. At the same time, the appearance of the

idiosyncratic graphic design that Maciunas was to impose on Fluxus gave

the magazine a distinctive look. The presentation of Fluxus 1

had also become more radical, for not only did it consist of diverse

formats and small objects, often in envelopes, but these components

were also fastened together with three large metal bolts. In addition,

the magazine was mailed in a wooden box branded or stenciled with its

title. The quarterly magazine had also been superseded by the concept of

Fluxus yearboxes. Whether or not Fluxus 1 lived up to George

Maciunas’ intention that it “should be more of an encyclopedia than…a

review, bulletin or even a periodical,” it certainly met the original

definition of the word “magazine”: a storehouse for treasures—or

explosives. This format was also very influential, affecting the

presentation of several “magazine” ventures later in the decade. (The

original meaning of “magazine” was exemplified even more emphatically

by the truly three-dimensional successors of Fluxus 1 , such as the Fluxkit suitcases and the Flux Year Box 2, containing innumerable plastic boxes, film loops, objects, and printed items.)

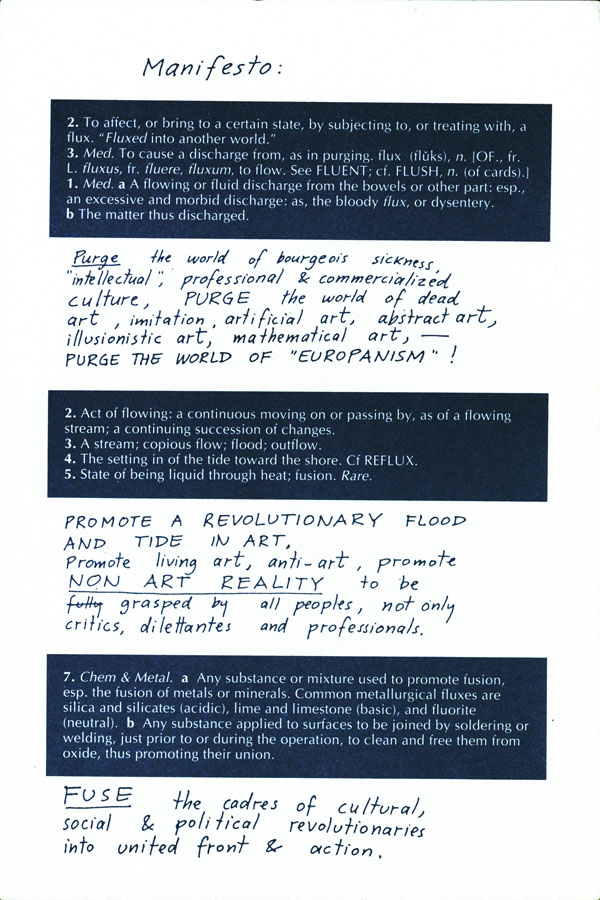

When George Maciunas consulted his

dictionary he found that the word “flux” not only existed as a noun, a

verb, and an adjective, but also had a total of seventeen different

meanings. At the head of his Fluxus…Tentative Plan for Contents of the First 6 Issues,

issued late in 1961, he rearranged five of these definitions to

explain the use of the term Fluxus, bringing to the fore the idea of

purging (and its association with the bowels). By 1963, these selected

dictionary definitions of “flux” could no longer encompass the

developing intentions of Fluxus, and Maciunas began to promote three

particular senses of the word: purge, tide, and fuse—each not amplified

by his own comments. These amounted to new working definitions of the

three senses, and were refined to the point where they could finally be

incorporated into a collaged, three-part Manifesto, together with photostats of eight of the dictionary definitions.

The aims of Fluxus, as set out in the Manifesto

of 1963, are extraordinary, but connect with the radical ideas

fermenting at the time. The text suggests affinities with the ideas of

Henry Flynt, as well as links with the aims of radical groups earlier

in the century. The first of the three sections of Maciunas’ Manifesto revels

that the intent of Fluxus is to “PURGE the world of dead art…abstract

art, [and] illusionistic art…” What would be left after this purging

would presumably be “concrete art,” which Maciunas equated with the

real, or the ready-made. He explained the origins of concrete art, as he

defined it, with reference to the ready-made objects of Marcel

Duchamp, the ready-made sounds of John Cage, and the ready-made actions

of George Brecht and Ben Vautier.

The first section of the Manifesto

also states that Fluxus intends to purge the world of such other

symptoms of “bourgeois sickness” as intellectual, professional, and

commercialized culture. In one of a series of informative letters to

Tomas Schmit, mostly from 1963 to 1964, Maciunas declares that “Fluxus

is anti-professional”; “Fluxus should become a way of life not a profession”;

“Fluxus people must obtain their ‘art’ experience from everyday

experiences, eating, working, etc.” Maciunas is for diverting human

resources to “socially constructive ends,” such as the applied arts

most closely related to the fine arts, including “industrial design,

journalism, architecture, engineering, graphic-typographic arts,

printing, etc.” As for commercialism, “Fluxus is definitely against

[the] art-object as [a] non-functional commodity—to be sold and to make

[a] livelihood for an artist.” But Maciunas concedes that the

art-object “could temporarily have the pedagogical function of teaching

people the needlessness of art.”

The last sentence of this section of the Manifesto reads:

“PURGE THE WORLD OF ‘EUROPANISM’!” By this Maciunas meant on the one

hand the purging of pervasive ideas emanating from Europe, such as “the

idea of professional artist, art-for-art ideology, expression of

artists’ ego through art, etc.,” and on the other, openness to other

cultures. The composition of the group of Fluxus people was exceptional

in that it included several Asians, such as Ay-O, Mieko Shiomi, Nam

June Paik, and Yoko Ono—as well as the black American Ben Patterson and

a significant number of women—and in that it reached from Denmark to

Italy, from Czechoslovakia through the United States to Japan. Interest

in and knowledge of Asian cultures were generally increasing in the

West at the time, and, in this context, are evidenced by Maciunas’

tentative plans in 1961 for a Japanese issue of Fluxus, which

would have included articles relating to Zen, to Hakuin, to haiku, and

to the Gutai Group, as well as surveys of contemporary experimental

Japanese art. (Joseph Beuys rather missed the point when he altered the

1963 Manifesto in 1970 and read: “Purge the World of Americanism.”)

The second section of the Manifesto,

which initially related to flux as “tide,” is really the obverse of

the first: “PROMOTE A REVOLUTIONARY FLOOD AND TIDE IN ART. Promote

living art, anti-art, promote NON ART REALITY to be grasped by all

peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals.”

Maciunas’ third section was “fuse,” and

read: “FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political

revolutionaries into [a] united front & action.” Inevitably most of

Maciunas’ time was spent trying to fuse cadres of cultural

revolutionaries, though not all the Fluxus people saw themselves in

this way. One of his tactics was the employment of the term Fluxus

beyond the title of the magazine as a form of verbal packaging, whereby

Fluxus people would benefit from collective promotion.

Toward this end, Maciunas established Conditions for Performing Fluxus Published Compositions, Films & Tapes, which

ruled that a concert in which more than half of the works were by

Fluxus people should be designated a Fluxconcert, whereas in a concert

where fewer than half of the works were by Fluxus people, each Fluxus

composition should be labeled “By Permission of Fluxus” or “Flux-Piece”

in the program. In this way, “even when a single piece is performed

all other members of the group will be publicized collectively and will

benefit from it,” for Fluxus “is a collective never promoting prima

donnas at the expense of other members.” Maciunas, therefore, was for

the “collective spirit, anonymity and Anti-individualism,” so that

“eventually we would destroy the authorship of pieces and make them totally anonymous—thus eliminating artists’ ‘ego’—[the] author would be ‘Fluxus.’”

Two years after the 1963 Manifesto,

George Maciunas produced another manifesto, significantly different in

tone. But in this new statement Henry Flynt’s ideas once again seem

evident. Maciunas introduces the topic of “Fluxamusement,” which

appears to be an adaptation of Flynt’s “Veramusement,” one of the

“successive formulations of [Flynt’s] art-liquidating position.” While

Maciunas still aspires “to establish artists nonprofessional,

nonparasitic, nonelite status in society” and requires the

dispensability of the artist, the self-sufficiency of the audience, and

the demonstration “that anything can substitute [for] art and anyone

can do it,” he also suggests that “this substitute art-amusement must

be simple, amusing, concerned with insignificances, [and] have no

commodity or institutional value.”

Later in the year, in a reformulation of this 1965 Fluxmanifesto on Fluxamusement,

Maciunas added that “the value of art-amusement must be lowered by

making it unlimited, massproduced, unobtainable by all and eventually

produced by all.” He further states that “Fluxus art-amusement is the

rear-guard without any pretension or urge to participate in the

competition of ‘one-upmanship’ with the avant-garde. It strives for the

monostructural and non-theatrical qualities of [a] simple natural

event, a game or a gag.”

The 1963 Manifesto, with its

talk of purging and revolution, did not include any mention of

amusement or gags, and yet the element of humor was not something

introduced suddenly with the 1965 manifestos; it had been an integral

part of Fluxus from its beginnings. Talking to Larry Miller in 1978,

George Maciunas observed: “I would say I was mostly concerned with

humor, I mean like that’s my main interest, is humor… generally most

Fluxus people tended to have a concern with humor.” (Ay-O summed up the

matter concisely when he said: “Funniest is best that is Fluxus.”)

In this same interview, Maciunas made

another intriguing remark, explaining that Fluxus performances—or

concerts or festivals—came about first because they were “easier than

publishing,” and second “as a promotional trick for selling whatever we

were going to publish or produce.” Even as early as the falloff 1963

he was able to say that festivals “offer [the] best opportunity to sell

books—much better than by mail.”

However, in spite of these beginnings,

one might say that ultimately the purest form of Fluxus, and the most

perfect realization of its goals, lies in performance or, rather, in

events, gestures, and actions, especially since such Fluxus works are

potentially the most integrated into life, the most social—or sometimes,

anti-social, the obverse of the same coin—and the most ephemeral. And

they are not commodities, even though they may exist as printed

prescriptions or “scores.” But when such scores and other paraphernalia

are encountered in an exhibition, rather than activated and

experienced through events, a vital dimension of Fluxus is missing.

There are some Fluxus works that can be experienced simply by looking,

because they work visually, and there are others that can be performed

by an individual as mind games. But many more works require that they

be performed through physical activity by one or more persons, with or

without onlookers. When works or scores such as these are seen or read

in an exhibition, experience of them can only be vicarious.

But Maciunas also said, in 1964, that

“Fluxus concerts, publications, etc.—are at best transitional (a few

years) and temporary until such a time when fine art can be totally

eliminated (or at least its institutional forms) and artists find other

employment.” He also affirmed that Fluxus people should experience

their everyday activities as “art” rather than such phenomena as Fluxus

concerts, for “concerts serve only as educational means to convert the

audiences to such non-art experiences in their daily lives.”

Although Maciunas himself, even by 1973,

was referring to the years 1963-68 as the “Flux Golden Age,” Fluxus

concerts, publications, and so on, however “transitional,” actually

lasted more than “a few years,” for Fluxus did not come to an end until

the death of George Maciunas in 1978. By that time the exact

composition of the Fluxus group had changed many times: some had left

early; some had returned; others had arrived late.

A few Fluxus people and neo-Fluxus

people believe Fluxus is still a flag to follow, while others believe

that “Fluxus hasn’t ever taken place yet!” George Brecht may have put

the matter to rest recently, when he declaredthat “Fluxus has Fluxed.”

But the elusive sensibility that emerged from a world in flux in the

late fifties and early sixties, and which George Maciunas labeled

Fluxus, has weathered the seventies and eighties and is fortunately

still with us. Today it goes by many names and no name, resisting

institutionalization under the name Fluxus even as it did while Fluxus

packaged pieces of it decades ago.

Labels: Clive Phillpot, Fluxus, Manifesto